Formal Verification

Introduction

Formal Verification is the process by which one proves properties of a system mathematically. In order to do that one writes a formal specification of the application behavior. The formal specification is analogous to our Statement of Intended Behavior, but it is written in a machine-readable language. The formal specification is later proved (or not) using one of the available tools.

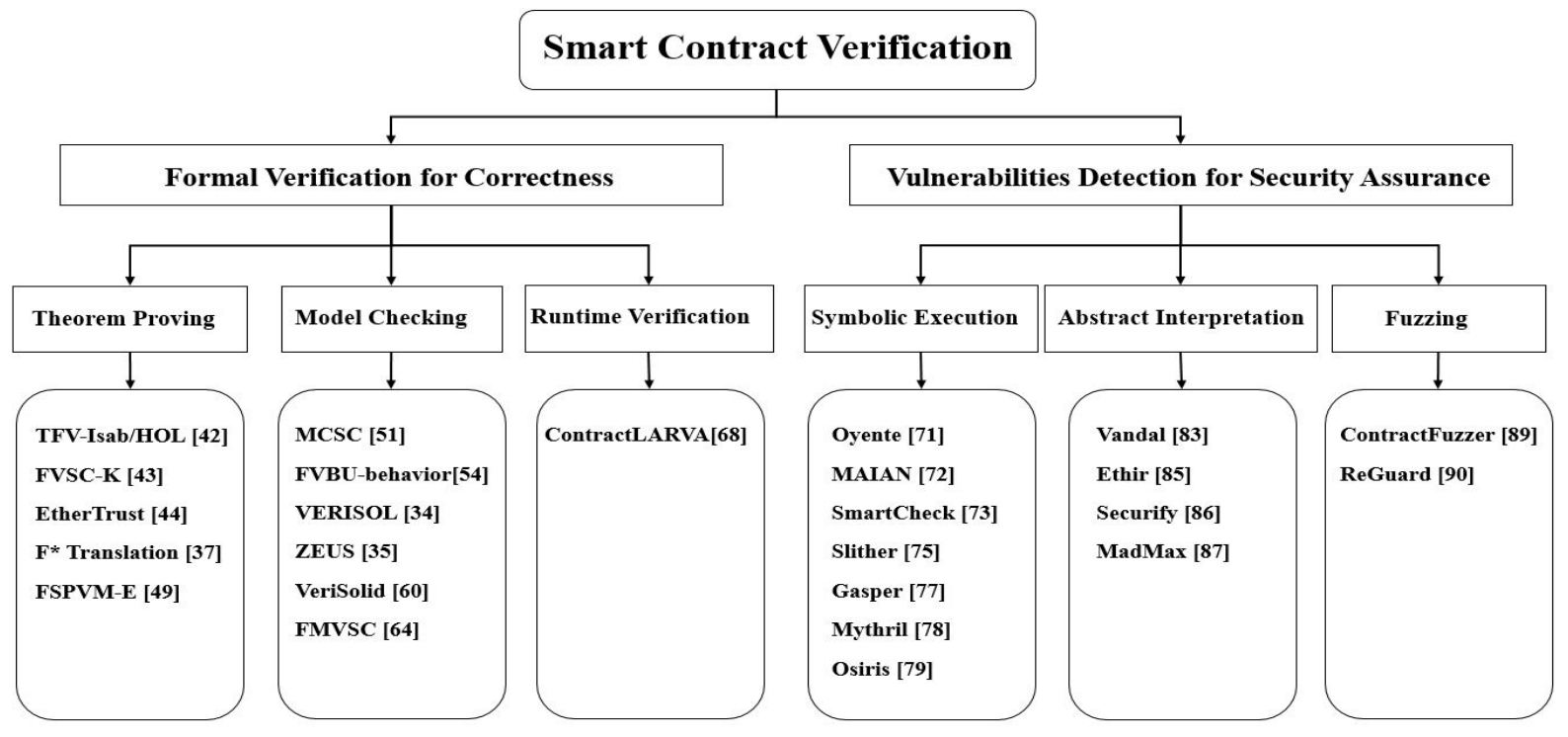

The correctness verification is about respecting the specifications that determine how users can interact with the smart contracts and how the smart contracts should behave when used correctly. There are two approaches used to verify the correctness: the formal verification and the programming correctness. The formal verification methods are based on formal methods (mathematical methods), while the programming correctness methods are based on ensuring the programming as code is correct, which means the program runs without entering the loop and gives correct outputs for correct inputs. We mainly focus on the formal verification approaches that is because formal verification is more rigorous and reliable.

In the case of smart contracts verification, we can improve smart contracts security by ensuring the correctness of contracts using formal verification. There are several projects aimed at creating formally specified execution environments (virtual machines) for various networks such as (Implementations in F*, Formal Ethereum Virtual Machine semantics in the K Framework).

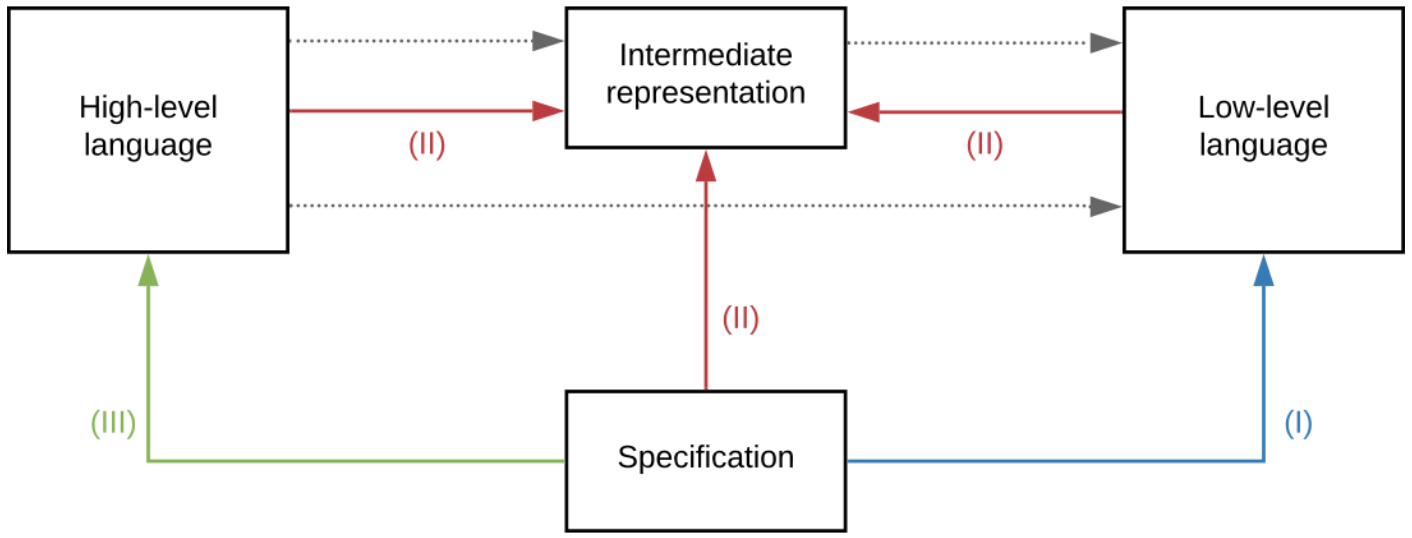

We may distinguish three major verification approaches :

(I) : a specification may be assessed directly at bytecode level. As contract sources are not necessarily available, this approach provides a way to assess some properties on already deployed contracts.

(II) : intermediate representations may be specifically designed as targets for verification tools such as proof assistants. This can offer a very suitable environment for code optimisation and dynamic verification according to specifications. The intermediate code representation may come both from compilation of a high-level contract or decompilation of low-level code.

(III) : some tools also reason directly on high-level languages. This approach offers a precious direct feedback to developers at verification time.

Contrary to Tezos and Cardano for instance, a formal semantics of the EVM was only described ex-post. And as the Solidity compiler changes rapidly, in the absence of formal semantics of the language that would allow correct-by-construction automatic generation of verification tools, the latter would need to follow the rate of change as well. These reasons make formal verification of smart contracts way harder on Ethereum than on other blockchains despite tremendous work initiated by several teams.

Two essential notions must be kept in mind to understand the challenge of formally verifying smart contracts :

Verification can be thought of as testing a set of properties (not all, only the ones we formalize) for all possible scenarios (including not only parameters but also message senders, blockchain state, storage, etc.). We don’t prove smart contracts, we prove some of their properties by proving their correctness according to a specification.

Proven correctness of all translations determines the level of confidence one can have in the entire framework. If formal verification of a program is performed on its intermediate representation, a backwards translation will allow for meaningful messages to be displayed in the higher-level original language. Furthermore, if translation to machine bytecode is not secure, then no one can formally trust its execution, regardless of the verification effort at other levels. To be considered valid, a proof must be generated within a single, trusted logical framework, from the level of the specification language to the virtual machine execution level.

As an example of functional specifications, some properties of interest for an ERC20 implementation can be:

a function level contract stating that the function

transferdecreases the balance of the sender in a determinedamountand increases the destination balance in the sameamountwithout affecting other balances. The sender must have enough tokens to perform this operation.a contract level invariant prescribing that the sum of balances is always equal to the total supply.

a temporal property specifying a property that must hold for a sequence of transactions to be valid, e.g.,

totalSupplydoes not increase unless themintfunction is invoked.

Pros and cons of formal verification

Formal verification of smart contracts isn’t easy. There’s a steep learning curve and a high entry threshold. A developer needs to undergo special training to be able to formalize requirements using formal verification tools.

Additionally, formal verification requires segregation of duties, in order to be effective. If the writer of the specifications is the coder of the application, the effectiveness of formal verification is greatly reduced.

Pros:

It doesn’t rely on compilers, this allows formal verification to catch bugs that were introduced during compilation or other transformations of the source code.

It’s language-independent, you can easily verify smart contracts written in Solidity, Viper, or other languages that may appear in the future.

A formal specification can work as documentation for the contract itself.

Cons:

It requires a specially prepared Ethereum execution environment.

A formal specification of the contract itself is required. Creating a formal specification is a long and difficult process and demands a lot of preparation from your development team. Specifying a program involves abstracting its properties and is thus a difficult task.

If there are any errors in the specification, they will be left undetected, every false requirement will be perceived as correct. Therefore, the verification won’t detect a problem with the smart contract. Verifying the correctness of a program implementation according to a specification is difficult as well.

Formal verification vs Unit Testing

Unit testing is usually cheaper than any other type of audit, as it’s performed when developing a smart contract. Proper unit tests should reflect the specification and cover the smart contract with the help of use cases and functionality the specification describes. However, unit tests are just as imperfect as informal specifications. Even if the smart contract code is fully covered with unit tests, the developer may miss some edge cases that could lead to bugs or even security vulnerabilities like overflows or unprotected functions.

Formal verification vs Code Audits

Formal verification is not, however, a silver bullet, or a substitute for a good audit. Also in the aforementioned industries, an audit is frequently conducted, including not only on the code base, but also on the formal verification specification itself. Flaws in this specification will mean that some of the properties of the application are not actually proven in the end, with bugs possibly going unnoticed.

While no smart contract can be guaranteed as safe and free of bugs, a thorough code audit and formal verification process from a reputable security firm helps uncover critical, high severity bugs that otherwise could result in financial harm to users.

Formal verification vs Static Analysis Tools

Static analysis tools are used to achieve the same goal as formal verification. During static analysis, a dedicated program (the static analyzer) scans the smart contract or its bytecode in order to understand its behavior and check for unexpected cases such as overflows and reentrancy vulnerabilities.

However, static analyzers are limited in the range of vulnerabilities they can detect. In a sense, a static analyzer attempts to perform the same formal verification with a one-fits-all specification that simply states, a smart contract shouldn’t have any known vulnerabilities. Obviously, a custom specification is much better, as it will detect each and every possible vulnerability within a given smart contract.

Tools

Manticore

Manticore is a dynamic symbolic execution tool, we described in our previous blogposts (1, 2, 3, 4).

Manticore performs the "heaviest weight" analysis. Like Echidna, Manticore verifies user-provided properties. It will need more time to run, but it can prove the validity of a property and will not report false alarms.

Dynamic symbolic execution (DSE) is a program analysis technique that explores a state space with a high degree of semantic awareness. This technique is based on the discovery of "program paths", represented as mathematical formulas called path predicates. Conceptually, this technique operates on path predicates in two steps:

They are constructed using constraints on the program's input.

They are used to generate program inputs that will cause the associated paths to execute.

This approach produces no false positives in the sense that all identified program states can be triggered during concrete execution. For example, if the analysis finds an integer overflow, it is guaranteed to be reproducible.

solc-verify

Solc-verify is a source-level formal verification tool for Soldity smart contracts, developed in collaboration with SRI International. Solc-verify takes smart contracts written in Solidity and discharges verification conditions using modular program analysis and SMT solvers. Built on top of the Solidity compiler, solc-verify reasons at the level of the contract source code. This enables solc-verify to effectively reason about high-level functional properties while modeling low-level language semantics (e.g., the memory model) precisely. The contract properties, such as contract invariants, loop invariants, function pre- and post-conditions and fine grained access control can be provided as in-code annotations by the developer. This enables automated, yet user-friendly formal verification for smart contracts.

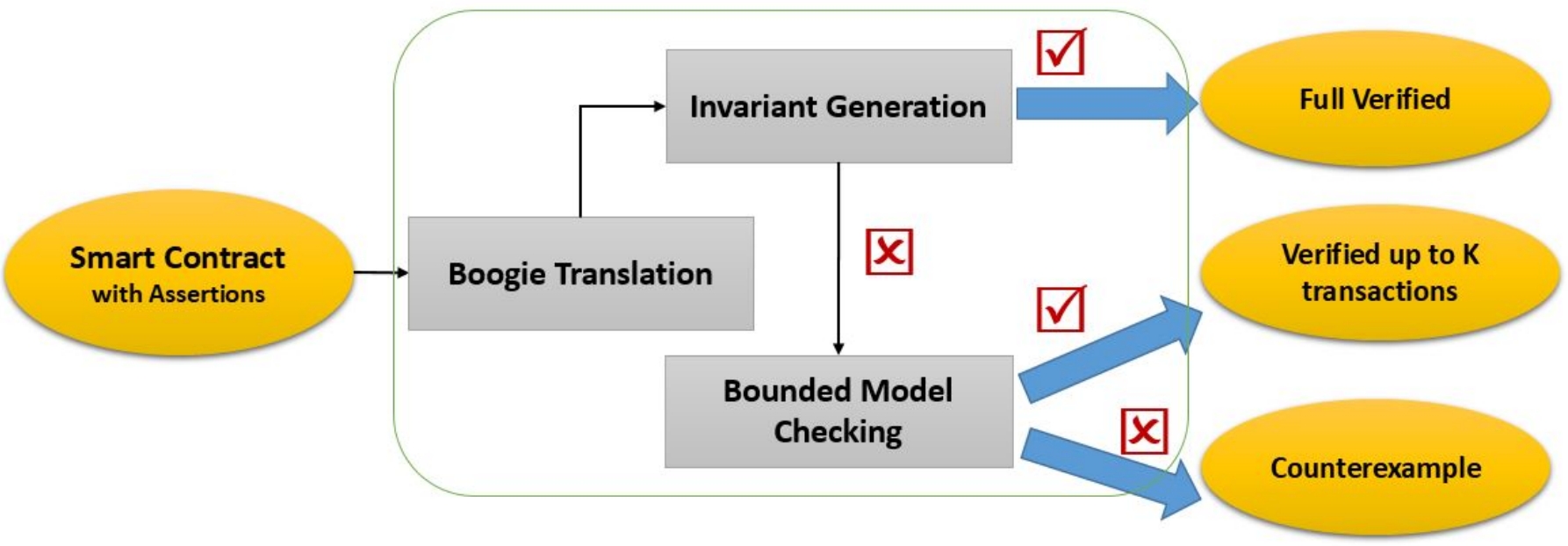

VeriSol

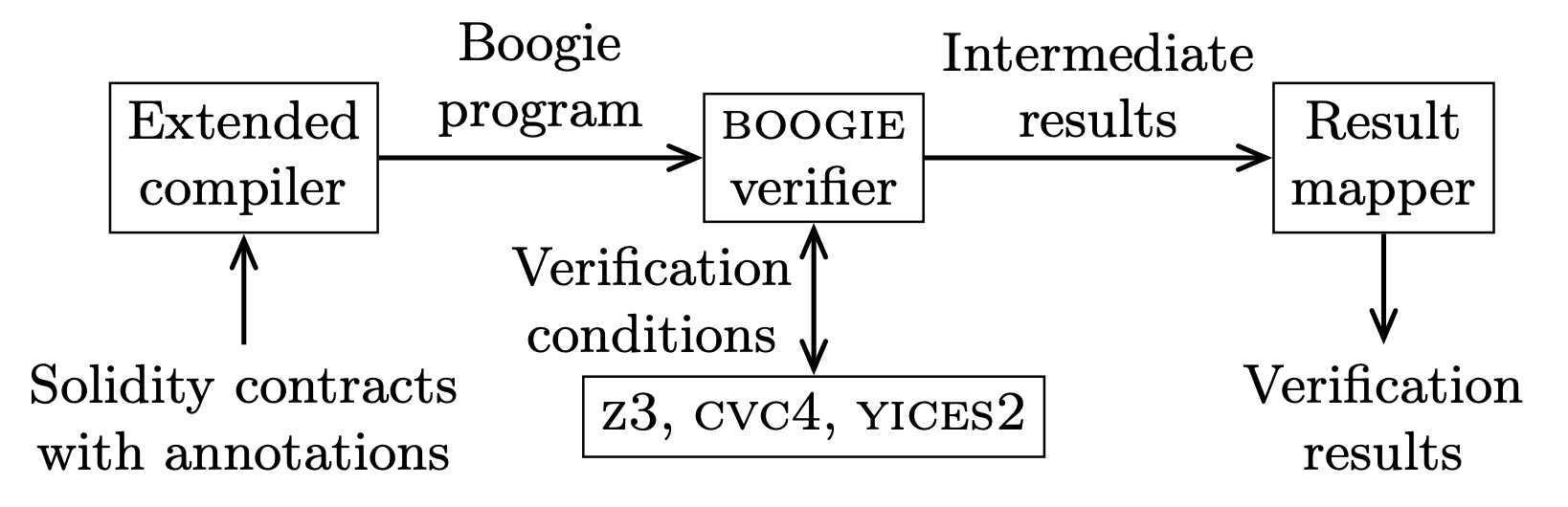

VeriSol (Verifier for Solidity) is a Microsoft Research project for prototyping a formal verification and analysis system for smart contracts developed in the popular Solidity programming language. It is based on translating programs in Solidity language to programs in Boogie intermediate verification language, and then leveraging and extending the verification toolchain for Boogie programs. The following blog provides a high-level overview of the initial goals or VeriSol.

This tool takes contracts written in Solidity and tries to prove that the contract satisfies a set of given properties or provides a sequence of transactions that violates the properties.

VeriSol directly understands assert and require clauses directly from Solidity but also includes a notion called Code Contracts (coined from .NET Code Contracts), where the language of contracts does not extend the language but uses a (dummy) set of additional (dummy) libraries that can be compiled by the Solidity compiler.

The function transfer equipped with assertions looks like this:

The spec is straightforward. We expect the balance of the recipient to be increased by amount, and that amount of tokens should be decreased from the balance of msg.sender.

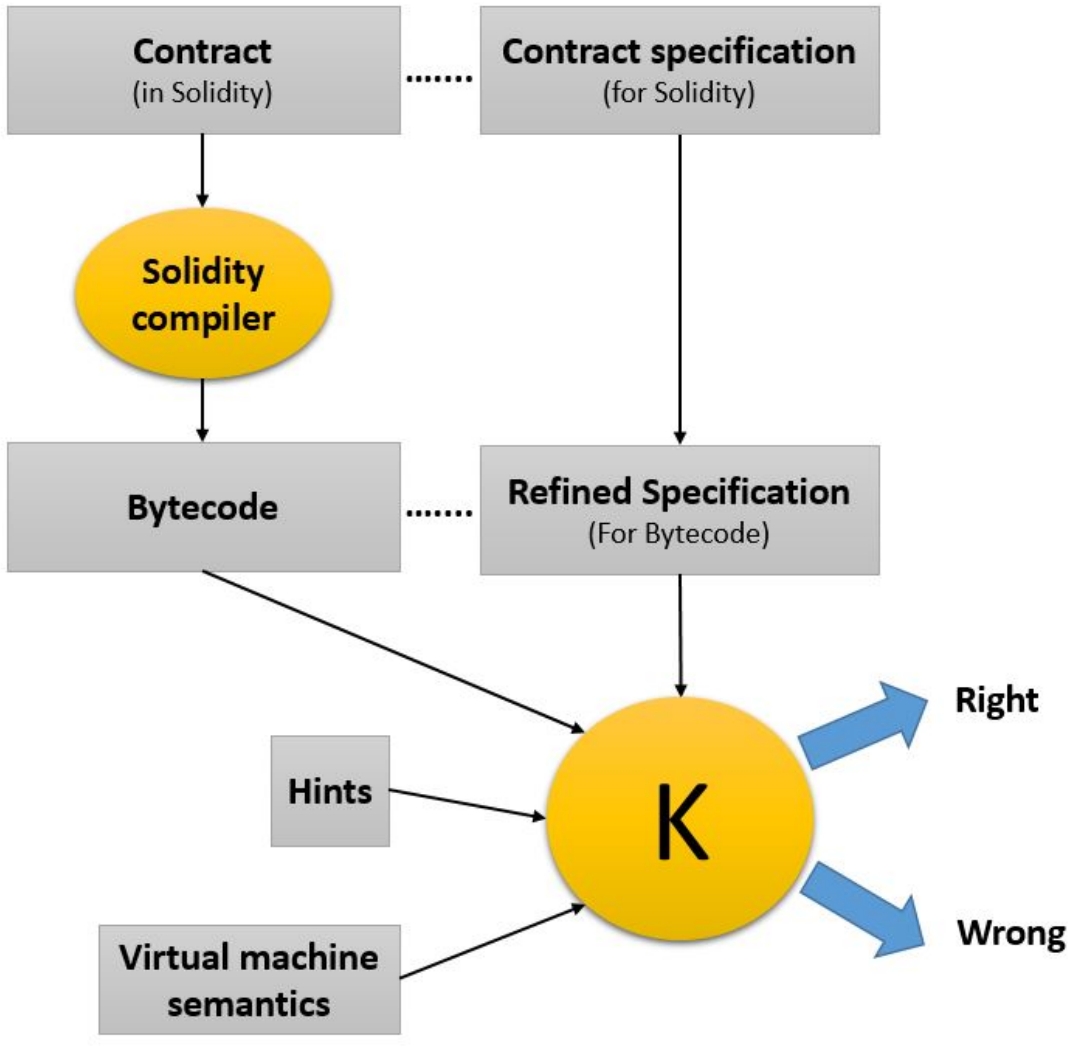

K Framework

The K Framework is one of the most robust and powerful language definition frameworks. It allows you to define your own programming language and provides you with a set of tools for that language, including both an executable model and a program verifier.

The K Framework provides a user-friendly, modular, and mathematically rigorous meta-language for defining programming languages, type systems, and analysis tools. K includes formal specifications for C, Java, JavaScript, PHP, Python, and Rust. Additionally, the K Framework enables verification of smart contracts.

The K-Framework is composed of 8 components listed in the following figure:

The KEVM provides the first machine-executable, mathematically formal, human readable and complete semantics for the EVM. The KEVM implements both the stack-based execution environment, with all of the EVM’s opcodes, as well as the network’s state, gas simulation, and even high-level aspects such as ABI call data.

If formal specifications of languages are defined, K Framework can handle automatic generation of various tools like interpreters and compilers. Nevertheless, this framework is very demanding (a lot of manual translations of specifications required, which are prone to error) and still suffer from some flaws (implementations of the EVM on the mainnet may not match the machine semantics for instance).

F* Translation

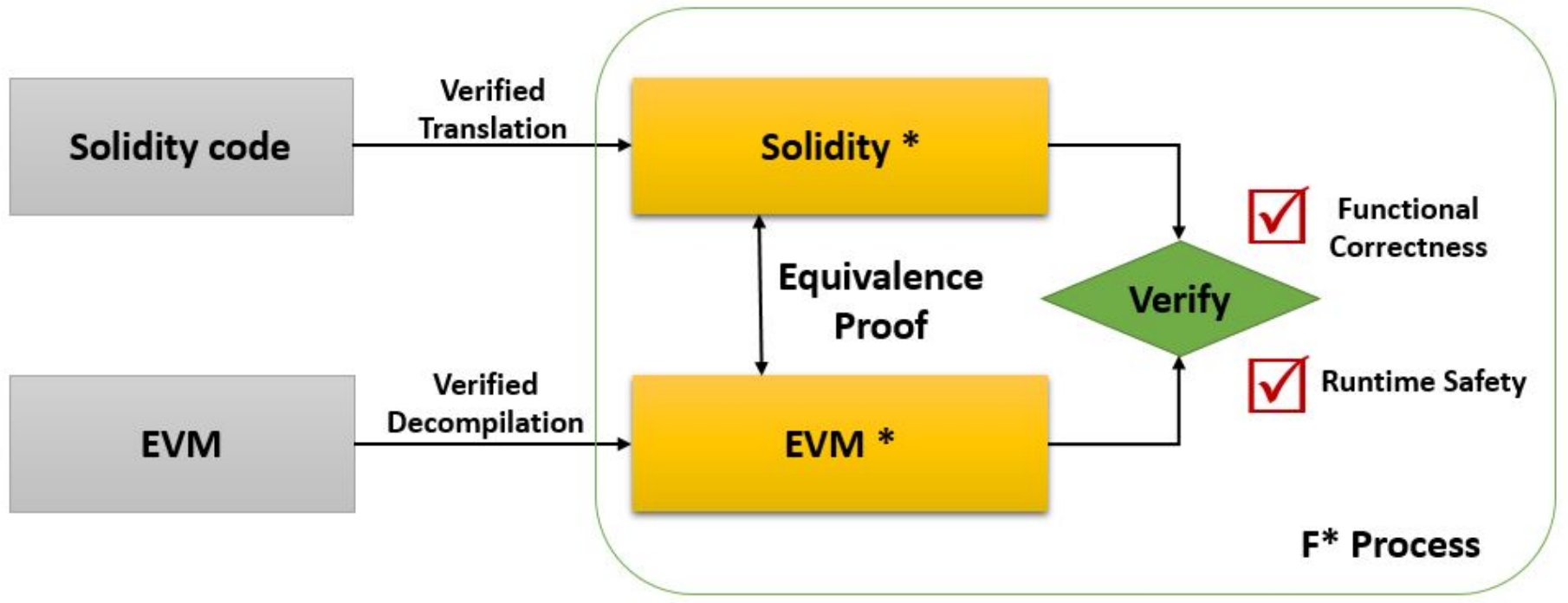

In cooperation between Microsoft Research and Harvard University, a framework is done to analyze and formally verify Ethereum smart contracts using F* functional programming language. Such contracts are generally written in Solidity and compiled down to the Ethereum Virtual Machine (EVM) byte-code. They develop a language-based approach for verifying smart contracts.

Two prototype tools based on F* are presented and a smart contract verification architecture is proposed and illustrated:

Conclusion

Formal verification is a mature science that could make a significant contribution to achieving this objective. But while some blockchains were designed with this goal in mind, verification of smart contracts on Ethereum, and in particular those written in Solidity, is far from obvious.

Resources

Last updated